Max Mason, In the Ballpark: The Per Contra Interview by Miriam N. Kotzin

Phillies Ballpark - Mural Study, No larger image available

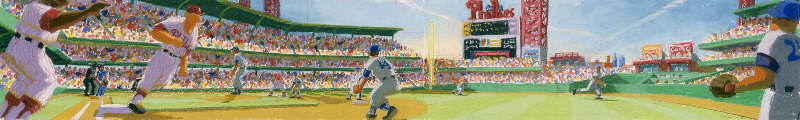

PC: Some of your baseball paintings are murals. (Other murals are views of Blanche Levy Park, Franklin Field, Boat House Row) Would you tell us a bit about the process of doing a mural? For which of these did submit ideas and sketches? Which of the projects came to you?

MM: The first murals I did were for The Penn Club in New York. That project came to me. The architectural historian in charge of the art for the building was a fan of my work, George Thomas. Since then it's been about 50/50 people coming to me and me going to them. As far as execution, the hardest part is getting everyone on the same page with the subject and composition of the image. Once the sketch is signed off on it's the mechanical matter of griding the wall and matching up the colors and shapes. You aren't really painting forms on the wall, just flat shapes that you trust will make visual sense when you climb off the scaffold and have a look.

PC: How do you work when you do the murals? Do you do the smaller murals yourself?

MM: I always do the work myself, no matter how big. Sometimes you need assistants, but they can create more problems than they are worth if you aren't careful.

PC: You quote John McCoubrey's American Tradition in Painting: "Nature, particularly in America, cannot be shaped or hollowed, as European painters, establishing an ideal order, have molded it. Spaciousness is at home in America, not only in our landscapes but in all our painting. Thus, figures in American pictures-like their viewers-are not given an easy mastery of the space they occupy. Rather, they stand in a tentative relation to it, without any illusion of command over it. My recent work embodies this concept. It looks to American realist, and regionalist painting of the 20's, and 30's with the emphasis on a spacious landscape and man's tentative place in it. Even when building large construction projects man is subordinated to the light and earth and vegetation of the landscape."

Which painters in particular do you think influenced you?

MM: The American realists of the 20's and 30's, Bellows, Hopper, Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent and recently the western artist, Maynard Dixon. My teacher Neil Welliver continues to be a huge influence. Lately I have been looking at artists associated with the west coast, David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, and Wayne Theibault.

PC: Obviously that point of view (McCoubrey's) speaks to something within you. Would you say something more about how you reached that point of view--“man's tentative place”?

MM: I think that harkens back to my early interest in geology. The forces of nature are beyond our control and complete understanding. Yet they are endlessly fascinating and beautiful. Life is a mystery, but the land and light on the land is tangible, solid and real.

PC: Is that reflected in the paintings of the solitary players on the field?

MM: Thank you for that question. Yes! I think it's very American too.

Left Field

PC: You've said, "I need intimate knowledge of a scene, I need to get comfortable there, to take possession of it in my head beforehand," he explains. "Then there is an initial flash of recognition when I find the right subject--a sort of epiphany. But the epiphany needs to be shaped, molded, pushed and remodeled." Can you recollect the process with a specific image? Say, in Approach or Hell Freezes Over?

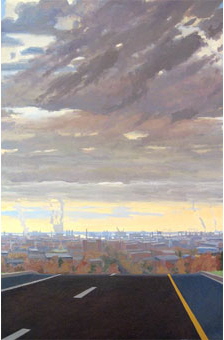

MM: Approach is a good example of what I meant. It began with a regular commute through Wilmington on I-95. There is a spot where the landscape opens up to a view of the city and the Delaware River below and beyond to the Chesapeake. I did several sketches of the spot, but couldn't figure out how to make a compelling large painting. It needed some kind of drama, the hint of a narrative to justify a large scale piece. Approaching the city from a different direction one day it came to me, make the road perpendicular to the river. It gave it a cinematic feel, Indians approaching from behind the hill above town. It was a simple change that completely transformed the mood and meaning of the painting.

PC: Your paintings on wood are translucent so the grain of the wood is visible. Would you talk with us about your choices there--finding the right panel, for example. What is your philosophy is behind that choice, the ways in which you go with the tradition, and your departures?

MM: For a time I sublet space from a wood worker. There were beautiful scraps of hardwood and finish plywood everywhere. Since my grandfather and father were and are woodworkers, and I'm cheap, or resourceful if you like, I would snag all these beautiful cutoffs. Cherry has a particularly beautiful grain. It can be a landscape, or a sky, or just breathtaking by itself. The simple still life, a solitary object, preferably something non arty, like a plastic coffee lid, a sponge, a lunch bag, became a respite from the huge mural project I was working on. I had a few rules; the object had to be something right there, I couldn't seek it out, you had to know it was painted on wood, and it had to be done in a couple hours. The idea of transforming something modest, a throwaway, into something permanent and of value in a couple of hours was especially appealing because of how long the mural was taking. I used these really small sable brushes, no. ones or twos.

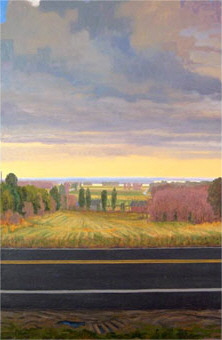

PC: Many of your landscapes include roads-- more or less prominently. (Double Yellow Line, Approach, Monument Valley from Gouldings, and Niobrara. Would you say something about that decision to include them as elements of composition rather than to exclude them? In at least one painting (Parking Available) you use a parking lot as the landscape, the mall building like distant mountains. How does this connect to your ideas of man's relation to nature?Citizen's Bank Park in the Sun

MM: This is our landscape today. It's a mix; asphalt, shrubs, industry, jet contrails. You have to really work to get away from it. And the lines on the roads are a great visual foundation for a painting, like linear architecture of a Diebenkorn. Woody Gynn has a fantastic painting of a road and a rock formation. It's all the same thing.

PC: I'm sure I've left something out--what would you like to say for which I haven't provided? Something about your prints?

MM: I have recently been doing pastels and it occurred to me that works on paper harken back to the geologic maps I used to love to study. They make sense of the landscape, were made of wonderful shapes and colors, kind of like a baseball diamond, simple but strong and interesting.Editor's Note: "Citizens Bank Park in the Sun", and "Man on Third" are examples of Pastels.

Man on Third

Approach

Double Yellow Line