Rulan Geiger, The Per Contra Interview by Miriam N. Kotzin

"An Illustration of a Book"

PC: You mention that you spent three years in Inner Mongolia during the Chinese Cultural Revolution as an art editor for the People’s Publishing House. Did the Cultural Revolution require you to leave where you were to go to the PPH? What were you doing as an editor—and how did it connect with your experience as an artist?

RG: Since the Communist took over China in 1949, Chinese citizens had no freedom to choose where to live and to work, same as the college graduates. We were assigned the jobs by the government depending on our family backgrounds and political behavior. I should graduate from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1967, but the Cultural Revolution started in 1966, the country was in chaos. The whole education systems were stopped. A few years later, my college moved to the countryside, a hard labor camp, guarded by military soldiers. From professors to students all worked on the field for 3 years. In 1973, the military assigned job for us, 6 years later than my graduation day. They assigned me to Inner Mongolia, because I was a counterrevolutionary. This was a punishment, a political exile. In long Chinese history, assignment of people to outside of the Great Wall was always an exile. I had to leave my husband and one-year-old son to go to Mongolia by myself. I could only go back to Beijing to see them once a year for two weeks. After I arrived at the Inner Mongolia People’s Publishing House at Huhohaote, they sent my to the countryside again for another year. Actually, I worked in the publishing house only for two years. I worked as an art editor. Most of the time I did illustrations of literature books. Also I designed the book covers and page lay out. After working hours, I could do my own art, but mostly I did political propaganda paintings. That was the only subject artist were allowed.

But in the 1970’s, I had a chance to go to the grassland to see the real Mongolia herding men and experienced the free spirit. That gave me a lot of inspiration and influenced my art importantly.

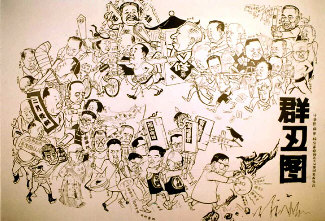

PC: Would you please tell us something about your cartoon, Crowd of Buffoon? Would you do a translation for us? Are the people in the crowd identifiable? Did you originally make the cartoon for publication? What went into that decision, and what hesitations, if any, did you have? Did it have any repercussions?

RG: I did this political cartoon in the end of 1966, in the Cultural Revolution beginning period. In the cartoon of Crowd Of Buffoon every character was real and important political figure of the Chinese Communist Party. At that time, they all had been over-thrown by Chairman Mao. In the picture, the figures arrangements were followed by the time line. The Cultural Revolution was started from the Ideological Bureau and Beijing City Government. I put the Propaganda Minister and the city leaders in the front of the cartoon, then followed the line was the Country Chairman Liu Shao Qi (sitting in a sedan) and Dong Xiao Pin (sitting on a chair) and so on. I was trained especially for figure painting. At college I did quite a few of my classmates cartoons and was popular. The Crowd Buffoon was my first political cartoon.

In general it was impossible for an artist to do any Chinese Communist Leader’s political cartoon, but the Cultural Revolution was a special chaos period. The old rule was broken. People had some degree of freedom. People could have their own organizations and publish their own newspapers. For an artist, the only art we could down was the political cartoon and poster. I did a lot of posters, other cartoons and huge murals of Chairman Mao. This Crowd of Buffoon was the most popular one. I was in my early 20’s, I did this cartoon in two weeks, then published it through an organization that I had joined. I caught each figure’s characteristic precisely and made a correct arrangement of the complicated political relationships between the figures. When this cartoon was published, it immediately became popular and quickly spread all over the country. Many years later, people still remember this cartoon. Later lot of books used this cartoon to represent the Chinese Cultural Revolution internationally.

PC: You have a lot of formal education in art--a BFA from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing in l967, worked for an MFA from the Graduate School of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in l978, teaching there in l980. How had CAFA in Beijing changed... and the sort of education you received? What were you looking for when you went back to school?

RG: I had a very long period of art education at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing. It started from Junior Art High School, affiliated with this academy. I studied at Art High School for 6 years and received basic training of Traditional Western Art. At the college level for 5 years, I specialized in Traditional Chinese Art. This academy was the best art college in China. It had five departments: Chinese Art, Oil painting, Sculpture, Printmaking and Art History & Theory. It was very competitive and difficult to receive admission. At that time the Academy had only 200 students and almost 200 professors. It was a noble academy. I was honored to have studied there and proud to be an artist. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, the school teaching materials were adopted from The Soviet Union and 19th Century French Academy System. Only exception was the Chinese Art department. In the academy, we could touch some of French Impressionist, but none of any contemporary arts. - Continued Below

"Crowd of Buffoon"

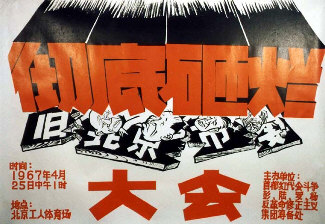

"Political Cartoon"

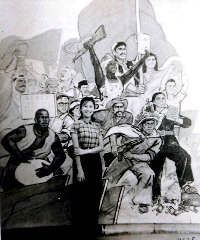

Rulan standing in front of a mural circa 1967

"Elegance"

During my junior year at the Academy, the Cultural Revolution started. My education was stopped. For almost ten years, I couldn’t do much art. I was exiled to Inner Mongolia. In 1978, The Cultural Revolution was finished. The Graduate School Program was started again. I applied to that program because I want to go back to my art field; also that was the only way I could go back to Beijing to live with my family. The entry to the program was very competitive. My class had only 14 students chosen from more than ten thousand applicants nation wide. The first year in the program, I did mostly studio work under Prof. Ye Qianyu, a well-known Chinese figure painter. The second year, I traveled all over China and visited the most important historical spots and saw the most beautiful sceneries. In Chinese art theory, it says: To walking ten thousand miles. It emphasize to watch, to memorize and to experience from the nature. During the two years training, I understood Chinese art at a mature level. So far, those two years were the best in my life.

PC: You received an MFA from the Graduate School of Fine Arts at the University of Pennsylvania in l984. By that time you’d already been teaching art in Beijing at the Central Academy. Why Penn?

RG: I knew of UPenn when I lived in China because my mother graduated from UPenn in 1938 (Master Degree of World History). I know UPenn is one of the well known Ivy League schools, but I didn’t know anything about the art school at Penn. In 1979, my younger sister came to the US to study at Wellesley College. I asked her to help me contact some art schools. UPenn was the first school she tried and was successful. For me, the only way I could come to the United States was to become a student and study at school. Also I wanted to learn Contemporary Art.

PC: What were some of the challenges you faced as a student who had just arrived from China? Language? (Would you be willing to tell here some of the story of your meeting with Neil Welliver that you told me last summer?)

RG: The most challenging was the language. Before I came to the US, I had no English. When I studied in high school, America was number one enemy for China. English was almost prohibited. So Russian was the only foreign language allowed to be taught in high school. At college, because I studied Traditional Chinese Art, I learned Ancient Chinese. After UPenn accepted me in 1980, I rushed to find a tutor in Beijing and started to learn from ABC. But the effect was little. In October, 1981, when I first met with the Chairman of the Graduate School Of Fine Arts at Penn, Neil Welliver, I could only smile, no word of English came out of my mouth. Neil said to my friend who was with me: “her sister cheated on me”. Because when my sister met with Neil, at the end of the meeting, Neil asked her: ”How is her English?” She answered: “Not as good as mine.” My sister was an English teacher. She has perfect English.

Neil came to my studio from Maine once every two weeks. Each time one of us would have to find an interpreter. Sometimes, Neil couldn’t find a Chinese interpreter, then he brought a Japanese. After Neil talked, the Japanese wrote down Neil’s instruction by Japanese characters. Then I could read it, because half Japanese characters are Chinese. Neil helped to arrange English classes for me. Also the environment gave me more pressure. In a half year, I could use English to communicate with people.

PC: What were the challenges you had as an artist as you moved from China to America? Did you adopt new techniques? At what cost to you?

RG: My poor English limited my communication. I felt that I looked clumsy and stupid. Second one was the art. When I first encountered Contemporary Art, I was shocked and couldn’t find the communication with it. My intuition was disturbing and disgusting. When I studied at Penn, I struggled and was unwilling to accept the concepts of the Contemporary Arts. I had to subjugate my art, that I worked so hard to achieve earlier in my life. The third one was to know who I am. In China, I was very proud to be an artist. But in America, I met a lot of artists that were struggling to survive to make a living. Also I struggled to pursue a career as an artist. The word of Artist almost is the same as the word of Unemployment. I am glad that my youth education gave me a strong self-esteem to be an artist. It supported me through my career.

PC: You studied contemporary Western art when you were getting that second MFA. How did that influence your painting? (I thought of Matisse in your use of patterned fabric.)

RG: Neil Welliver was one representative artist of the Contemporary American Realism. His art school had strongly influenced the Graduate School Of Fine Arts at Penn. I felt lucky to study with Neil. His realistic style of art made me understand his school easier than other Contemporary Art Schools. Three years of study at Penn gave me a transition time to practice and understand some elements of the Contemporary Arts. I started to change the way of thinking, absorbing and expressing my art.

After lived in the US a longer time, from visually to mentally I became comfortable with the Contemporary Art forms and understood their history and theories. Sometimes, these art works could surprise me and make me laughing and exiting. Even though I may never be philosophical and psychological the same as some of the Western Contemporary Artists, this whole art area opened my mind. With both a hate and love feeling, I fund such a broad way to doing art.

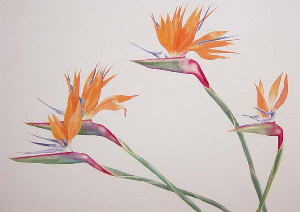

PC: What are some of the traditional elements or principles that you learned in China that you retain in your work? Do these occur when you’re not painting on silk? Do you use the symbolism, the traditional iconography of flowers, birds and plants in your paintings? (I’m thinking of the flowers you include in your painting Youthful and Flowers in the Vases, or the bamboo and butterflies and choice of flowers in the murals.) If so, would you talk about that element? Are you thinking of peonies as a symbol of prosperity or bamboo as strength in face of adversity? Roses? Fish? Parasols?

RG: My esthetical standards are strongly influenced by Chinese. Those standards are deep-rooted in my mind, because the preconceived ideas keep a strong hold. For example, when I design a composition of a painting, I often prefer to use a flat way to arrange the space, either in black and white or in colors. Also I like the details and often emphasize them and put them equally with other parts of the painting. The forms and lines often attract my attention more than the colors. I like the strong, simple and delicate effects. Silk is one of my favored materials because it has a special effect other materials cannot compete with. I also like working on the canvas, cotton, watercolor paper and rice paper.

Symbolism is one important element in Chinese Literati Art. This art school’s feature was to use ink with free-hand style working on rice paper. Literati Art is a mature art style in Chinese art history, started about a thousand years ago. It developed Chinese art from the iconography to the subjective world. Those scholars gave the certain objects a meaning symbolic of themselves. When they painted these objects, they often combined poems to express their personal feeling and ideas. For example, bamboo was one common object in Literati Art. The Literati used the bamboo hard quality to be symbolic of their noble and unsullied temperaments. The Bamboo’s hollow trunk was symbolic to Literati’ as the self-disciplined gentleman. Plus the beauty of the bamboo has attracted the scholars repeatedly to paint bamboo for over a thousand years and developed many art styles. The Literati Art had a profound theory and sophisticated technique. At the same time they created Chinese esthetic element. So when I saw certain things, often I would automatically relate to those elements.

I had a true story: In my current house, we had a bunch of bamboo along the driveway. Year to year the bamboo grew bigger and bigger and all over the places. My husband hated them (he is a Caucasian). But I always had feeling with the bamboo and was determined to keep them. I spent a lot of time and labor to fix and maintain them. Eventually, the bamboo grew too wild. They had crossed under our ten foot wide drive way and grew under my house. They took over the all ground. We had to cut them off. When the day the bamboo were gone, I was very sad and wrote an essay “Offer A Sacrifice To Bamboo.” (This essay is on my website)

When I choose the objects of my flower painting, first to come to my mind is the visual element. I see things, then have feeling with it, then try to carry the impression and the feeling to my painting. The symbolism is not a propriety element in my choice of the object, but when I present the painting, I may add some of the symbolic meaning to it. - Interview Continues

"Long Life of the World People Revolution"

"Golden Age"

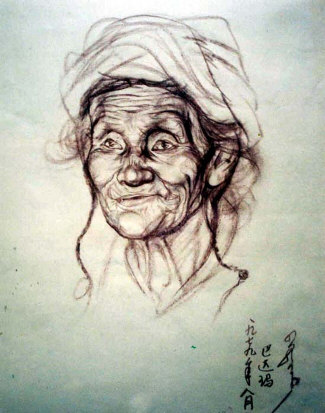

"Life Drawing of a Mongolia Lady"

"Chairman Mao"