Eric Fischl, The Per Contra Interview by Miriam N. Kotzin

Tumble

2001

Lithograph on paper

43" X 31"

Edition: 32

Artist's Proofs: 6

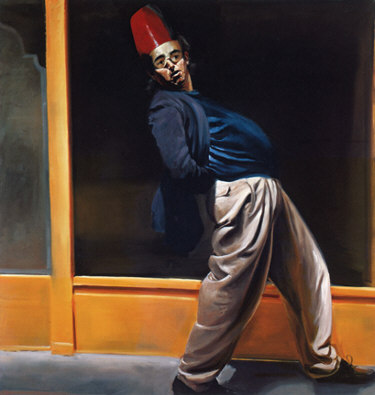

Portrait of the Artist

1998

Oil on Linen

72" X 68"

PC: If painting could speak, like Mark Twain, it would say, “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” But when you began your work, a prevailing idea was that painting was dead, or, at least, moribund. So at that time taking up the brush especially to do figurative painting, was fairly courageous.

Is it possible that painting was on its death bed? If so, what revived it? Do you think that the art world has some idea in it today that like “the death of painting” will, in the next decade or so, prove to be mistaken?

EF: The death of painting is a metaphor. It is a way of speaking about how our relationship to the sacred, to abstract, or to the purely human has changed.

The argument is whether the change is an evolution or a devolution. Painting as an object of great complexity and power stands at the center of this debate. There is no form in art which is greater and more difficult and more historically laden than painting. Any artist who takes themselves seriously on the historical scale must in some way engage painting’s shear breadth of creative invention. There is no medium that is able to express more and with greater variety than what painting has done and continues to do.

PC: You’ve distinguished between pose and posture, “Pose is an abstraction of the body and is something that artists have used to deal with formalistic problems in painting. It’s about aesthetics, beauty and proportion, about line and shapes expressed through the forms of the body. Posture is body language; posture is the shape the body takes based on the accumulation of experience. So its through posture you gain insight into the person.” Is your use of pose and posture different in narrative painting than in portraiture?

EF: I don’t use “pose”. I only use “posture”. Body language is present even in the still moment. It is the way one sits or leans, hunches or fidgets. I try and get my portraits to capture or at least intimate a narrative the sitter has with themselves.

PC: You’ve said that you know when a work is finished when you’re “looking [at it] and asking, ’What the hell’s going on here?’ and want to try to figure it out from the audience’s point of view.” Is this especially true of narrative paintings, or do you think that works for, say, portraits, too?

EF: A painting is a painting. When it is finished is a problem all genres share. What I mean by my statement is that there is a certain point I reach when I stop “fixing” the painting. I stop worrying whether this edge is too soft or that color is not intense or saturated enough, etc., and I begin just looking at the painting the way someone would who is seeing for the first time. I want the painting to precede the language used to describe its experience. My process is one in which I paint backwards from language and intellect, not away from, but more of a retracing the steps that took me from experience to thinking about it.

PC: In an interview with Robert Enright you described how you ‘got’ Max Beckmann’s Departure, by standing in front of it and telling yourself what you saw, working your way through the painting. You said, “I think the thing that excited me most was the revelation that however much you put into a painting, someone will get it out, and that you can trust you know more than you know when you read it because so much of it is associative.” Do you recommend that as a way for people to look at your paintings?

EF: Yes. I think the viewer should look at all art that way. It is misguided to think that the artist knows more or has secret knowledge of their work of art. When a work is finished it contains the entirety of its meaning and significance. Experiencing a work of art is an act of possession and the viewer should feel confident the meanings they draw from that encounter are completely valid. The problem art has had stems from that aspect of modernism that attempted to invalidate the viewer. This reached its highest point of absurdity in the late 60’s, early 70’s with conceptual art.

PC: What if the audience has a terrible misunderstanding, as has happened with your sculpture Tumbling Woman? [The sculpture, created as a response to 9-11 was removed from Rockefeller Center—where it was to be displayed for two weeks—after only a few days. During that time it was put behind a screen after an art critic wrote about it, saying, wrongly that it described the moment of impact.]

Tumbling woman maquette

2001

Bronze

12" X 18" X 14"

Edition: 5

Artist's Proofs: 2

EF: The misunderstanding of Tumbling Woman was due to misinformation by the yellow journalist, Andrea Peyser. She never saw the sculpture and wrote a description of it that was incorrectly. She also wrote about my intentions for the piece without talking to me so she projected what my intentions were.

Art must be experienced first hand in order for someone to “know” what it is about. Jpegs, newspaper photos, slides just don't cut it.