April Gornik, The Per Contra Interview by Miriam N. Kotzin

Gathering Storm

2003

Oil on Linen

22" x 31"

Slow Light

1992

Oil on linen

57 x 120

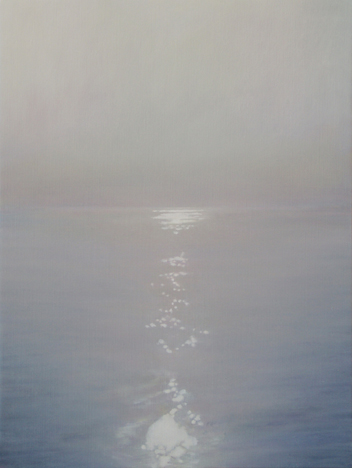

Light on Water

2005

Oil on Linen

32" X 24"

Woven Trees

2006

Oil on Linen

50 x 36

PC: You started out as a conceptual artist, using text in your work and then moved to painting landscapes. You’ve said in an interview with Robert Enright, “...like it or not—all artists portray the artists [that is, they portray themselves].” Do you think that’s true in conceptual art? In landscapes? And, if so (you could see this one coming, I’m sure), how do you portray yourself in your landscapes? Is that the dialectics you talked about in the interview with Michael Rush: your conflicting desires “the Martin Johnson Heade part of me that wants stillness and a certain kind of clarity and then there’s another part of me that needs turbulence and moves towards Turner...sometimes even within the same painting”?

AG: The choice to make conceptual, abstract and/or landscape art reveals something about the artists who make it. Obviously the result is not necessarily direct self-portraiture, but can be close to it. In the sense that my landscapes are emotionally expressive of, and specific to me, they "portray" me. The conflict you mention is essential to what I'd consider a kind of truth about myself, and about the dimensionality being human, i.e. that there's both an erotic and a thanatopic component, or other versions of that dialectic, that is necessary for a work of art to be fully expressive. The best work I make contains both at once. Not equally, necessary, but both are represented.

PC: In moving away from conceptual art towards the end of your BFA, midway through the two semesters in Nova Scotia, you said in the Rush interview that you were “dissatisfied with way my whole art progress was going, and especially in talking to one of the other faculty members there who was having a similar crisis I sort of worked myself out of that intent...and began trying a lot of other things...” Would saying more about that series of discussion be a violation of privacy? Would you mind saying who that person was and what role your teacher had in determining your decision?

AG: Not at all, I had the good fortune to have Richards Jarden as my studio advisor in my year at NSCAD [Nova Scotia College of Art and Design]. We had many discussions about applying theoretical texts, like those of Piaget and Claude Levi-Straus, to art-making, which is what I'd been doing. We were both interested in revitalizing what we thought was a dead end that painting had reached, and content was a big part of those discussions. I didn't arrive at painting landscapes during those two semesters, nor did I "solve" my dilemma, but I was able to reject the activity of illustrating structuralist texts as a means of self-expression at that time, and began to move toward something more personal. I wouldn't have called that move a decision, exactly, rather more a revelation.

PC: How did the process of teaching students influence your painting, such as consciousness of and exploration of technique (density of surface, details, amount and kind of paint, brushwork)?

AG: If you are referring to the time I'd worked with adult painting students after I graduated from NSCAD, I would say that the principal influence came about in trying to describe to them why they should like minimal and conceptual work, which they found puzzling, and realizing that I personally was finding it lacking. I didn't reveal that to them, but tried to be fair and to communicate to them what was powerful and interesting about minimalism and conceptualism, because I was trying to improve their sense of art history in general, and contemporary art history in particular. Describing art movements while showing them slides taught me a lot about what I really thought about a lot of different kinds of consciousness in art-making. I myself wasn't acute enough as a painter, having really only recently gotten into it seriously at the time, to have been able to make much sense of exploration of technique, although I could tell them where they were engaged or being perfunctory in their own work, and could encourage them to remain aware of their own better proclivities. The class was not for beginning painters, anyway.

PC: You’re not a plein air painter, and your early paintings—ironically begun when you moved to Manhattan, I believe—were imaginary? You’re known for your large landscapes—was the first one you did (not the sticks that you painted on the boards glued together) enormous?

AG: The first landscape paintings I did were in Nova Scotia. I began on boards, "graduated" quickly to plywood, and then in 1980 in New York realized I wanted to make a painting that was bigger than a full sheet of plywood (4' x 8') and reluctantly switched to stretched canvas. I don't know how enormous 4' x 8' seems, but I felt a kind of natural impulse to make paintings that felt like they experientially surrounded the viewer. It took a while to realize why I wanted them to be that scale, but most of the understanding I've arrived at with my work has been retrospective and not immediate.

PC: You began using photography when you first visited the desert. What was there about the desert that made you decide to use a photograph as a reference, rather than painting a version of what you remembered?

AG: The work was imagined, exclusively, until I went to the American Southwest for the first time, which was in 1980, and saw the desert for the first time in my life. I had a camera, took pictures, and realized that no dream or vision I'd had was much stranger than that. Since I had been painting a lot from dreams, there was a sort of natural surreal (if you'll pardon the oxymoron) quality to the work, and the desert had that in spades. I felt like I was looking at a dream landscape.

PC: You’ve mentioned the decisions in landscape painting: the perimeter, the type of light. I was struck by the words you used in describing the light: “passing,” “falling,” “happening,” “fading”—all words of transition. In other words, not static. The curator of the Neuberger where you’ve recently had a huge mid-career retrospective, Dede Young pointed out that in many of your paintings ambiguous moments “prevail as a psychological state of the moment where something is changing or happening and the viewer, depending on who you are will see it as foreboding or relieving.” You’ve said paintings are “vulnerable to interpretation.” Do these all go together? or do you want to comment on the observations separately?

AG: Your question nicely sums up what I think about the "moment" I like a painting to contain, which is both active (in the sense that it's ambiguous and, as I said, should be vulnerable to interpretation) and passive (in the sense of it being a moment frozen in time, and also because of that, vulnerable to interpretation). I think of paintings as being objects, and even states if you will, that invite interactivity. They provided the first experience of virtual reality, and still remain the best, in the sense that the hand of the artist remains in them, provoking a further intimacy because the viewer can react with the history of their making as well as the imagery present.

PC: You began working with a computer after you were given a computer for Christmas—in, what year was that? Or was it that you were given the computer because you’d started working with one and wanted to do more? As I understand your process, you Photoshop and collage a number of photos, some yours, some that you find, and through collaging transform them. Do you continue also with the sketches in addition? Have you considered saving the intermediate steps on disks so there will be a record or your process?

Does this new method make the blank canvass less formidable?

AG: I was given a computer for Christmas because I was tired of being so disorganized. I knew other people, including Eric [Fischl], who were keeping track of their work on their computers, and I wanted to do that as well and not just depend on my gallery. I think that was Christmas 1994. I had a scanner to make little images for my filing program and at one point I stuck a photo I had of a painting I'd been working on in it and then started horsing around with it, tentatively, in Photoshop. I made some corrections on it and suddenly realized I had a great sketch tool at my disposal. I'd made small sketch after sketch previously, correcting as I went along, and the worst thing about that was continuing my thought process at the speed that I could draw as I'd make changes. Photoshop speeded those decisions and made some interesting perspectival changes possible. I do collages from photos I've taken, and ones I've found, and/or downloaded from the internet.

PC: In an interview with L. Kent Wilgamott you said as to why your landscapes weren’t “normal, easy pictures,” that “I think they express the Other for me. For me, landscape is the Other. I’ve heard it theorized that for men, women are the Other. For me, maybe landscape is the Other.” And in a radio interview with Michael Rush, you asserted that “Nature for me is the other. It represents the great thing that’s the most unlike me I can imagine...” Those interviews weren’t far apart, nor were they long ago. Is it a matter of mood, or were you in the process of finding a new way of articulating what’s happening in your art. (That seems to be a constant, a periodic or ongoing re-examination for everyone who’s seriously working at something.) Where do you situate yourself with Nature now?