Alex Katz - Per Contra Interviews

Tom Boutis, a friend of mine, was one of those painters. Tom and I had a two- man show at the Tanager Gallery in 1957. I felt I was going to meet her and we would connect.

PC: You’re so conscious of clothes and fashion, something you said your father taught you, do you remember what Ada was wearing? What was it about her that first attracted you to her? Do you remember your first conversation?

AK: She wore a beige sweater that fit loosely, but showed her waist, with a gray slim skirt and high heels. After the opening a group of us went to the Chuck Wagon cafeteria and she smiled. I had never seen anything like it. The next week we danced at a party and that was it. She was the best social dancer I ever met.

PC: What did you say when she asked you why you weren’t painting abstract? This could have been a real deal-breaker...but instead...

AK: Ada is smart and inquisitive about radical art. She got to Samuel Beckett before the poets I knew did. It didn’t take long for her to figure out what I was doing.

The most amazing thing to me is that she makes no social mistakes and has great taste.

PC: How long did you know her before you painted her portrait? What do you remember about that experience? How did you feel about showing her what you’d painted? Was it different from other portraits—you’d done up to that time? You’ve done many more than forty portraits of her. Will that first one be one of the portraits in this show?

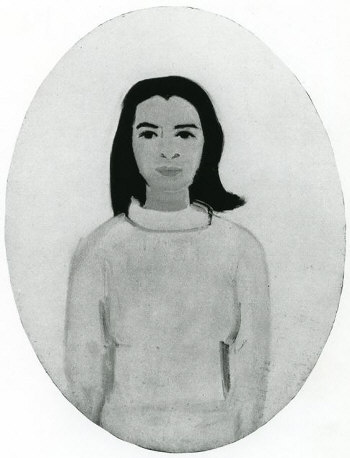

AK: I had decided to paint portraits around the time I met her in 1957. I had already begun several. Ada was a perfect model. It took me all winter to get a likeness that I liked. It’s in the show at the Jewish Museum, Oval Ada.

PC: Many of your portraits of Ada are titled with some article of clothing Black Scarf, White Hat and The Black Dress which has Ada in the same dress in six poses. One of your favorite artists, Matisse, titled one of his paintings The Roumanian Blouse, was that an influence? You mentioned that clothing, fashion, style is important, and when something goes out of style then the work of art can be great. How does that connect with calling attention to the clothing in titles?

AK: Using clothes as a title is an attempt to lead the viewer to see the painting in a less local way.

Oval Ada

1958

Oil on Linen

24 3/4" X 18 3/4"

Colby College Museum of Art, ME

Visit the Alex Katz website for more information and a complete bibliography.

Morning With Rocks

1994

Oil on canvas

126" X 96"

AK: Wet in wet developed from sketches I did in Madison Square Park in New York, in 1964. Wet in wet enables me to get the directness of my sketches on a large scale and to get multiple tones with a single brush stroke. I get a fluid surface on a large size.

PC: You’ve said that you do lots of preparation for the big painting, including getting the lines transferred with pouncing, pre-mixing all the paint and laying out the brushes. This painting is a good example to tell our readers what you can do with oils that you couldn’t do with acrylic: you didn’t get out a roller and do the ground of the yellow sky. When you did Seagull in the Morning Sun, what yellows did you use in the sky? (say lead-tin yellow? cadmium yellow? chrome yellow?) Do you choose them for their translucence? What sort of brushwork did you use and did it change much over the canvas?

PC: When you were doing your small collages, did you see the first one as a kind of experiment? What kind of paper did you use---did you have to go out and hunt around to find it? What did you have in mind in working with them? Joseph Albers had come to Yale several years before that...were his theories about color in the air? You said about your show of collages, “I wanted to kick the machos on their asses.”

AK: The collages were conceived as a reaction to cubist collages and Matisse’s cutouts. They had to do with time past, nostalgia. I made drawings on the spot and some time later tried to find the equivalent in paper to what I remembered. In the beginning, I used mostly hand colored papers (watercolor). As they progressed, I used printed colored paper more and more. Albers never interested me.

Red Smile

1963

Oil on Linen

79" X 115"

Whitney Museum

February 5:30pm

1972

Oil on linen

72" X 144"

To a painter the interest would be how the image is conceived and constructed—the energy of the paint, the special effect of the pigment.

PC: Some stills from the film of you painting, Five Hours, show you wearing gloves while you paint. How long have you been doing that? Just with the large paintings? Why are you wearing them (chemicals? toxic paint?). What accommodations did you have to make to wearing them when you were handling the brushes.

AK: I started wearing gloves 10 or 15 years ago. I am not an extremely neat painter and I don’t like to get my hands dirty.

PC: You’ve said that when you were teaching as a visiting critic at the University of Pennsylvania you used to go to the University Museum a lot. What galleries did you spend most of your time visiting? Why those?

AK: The Museum of the University of Pennsylvania has a terrific Egyptian collection.

PC: Critics have mentioned the influence of “floating world painting” and you’ve said you have an affinity for Thuthmose’s sculpture of Nefertiti. Could tell us more about that?

AK: Utamoro, the Japanese artist, has been an inspiration since the fifties. His world seems to be the one I live in. His 6 women is my February 5:30 pm.

Tuthmose is tops. He can model with the delicacy of Rafael. (Brooklyn Museum: Tuthmose’s mother and child, for example). He brings elegant portraiture and style together. He makes carvings of animals with a line that brings them to life.