A New Sacred Space: Michael Somoroff’s Illumination I by Donald Kuspit

But what makes Somoroff’s sacred space truly original—a serious departure from both Gothic and modernist traditions, and an unusual embodiment of faith—is its integration of modes of consciousness usually regarded as incommensurate. The Gothic church embodies profound faith, more crucially, it synthesizes the scholastic view that faith is a superior form of reason, an idea implicit in the “cunning” geometry of its hierarchical structure, to use the Abbot Sugar’s word—pure reason is in principle the topmost rung in the hierarchy of consciousness (and spiritual value) [the architectural hierarchy corresponds to it, marks the steps up its ladder], implying that faith can be achieved by intellectual means, that one can argue or reason one’s way to belief in God—and the more emotional view of faith as all-absorbing aspiration toward the divine, climaxing in mystical illumination and communion with the divine, a sort of direct if temporary coming into its living presence.

This numinous, consummate experience of “seeing the light,” the dramatic fruit of pure faith—faith unadulterated by reason, as it were—brings with it the realization that all creation is sacred or divine. Being is the miraculous gift of God. One is surprised by being, and surprised by God, to whom one completely dedicates one’s life in gratitude for the miracle of being, an expression and revelation of God’s own being. Thus “the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty” of the whole church, to use the Abbot Sugar’s words again, symbolizes “seeing the light” and hopefully catalyzes an experience of “seeing the light.” The light that floods the church invites one to do so, invites one to see divinity in the light one actually sees, to experience the light that pervades the interior as sacred light. This revelatory light makes the church’s interior sublimely beautiful, and highlights its physical beauty, the beauty of its structure and material splendor. The Gothic church is indeed the body and soul—mind and matter—of God, and as such sacred in every detail.

Now Somoroff’s sacred structure does the same thing, in a very different way, as the Gothic structure: Illumination I integrates the opposites of spiritual reason and spiritual feeling—and does so more seamlessly than the Gothic church, which is another reason it is original. It also embodies spiritual aspiration in its structure. It is also materially grand and geometrically sophisticated. But it does something that the Gothic church doesn’t do: Illumination I does not simply “show” or exhibit the light, the way it is “shown” or exhibited in the interior of St. Denis, where it appears as inarticulate “mystifying” atmosphere, but articulates its “inner” rationality or structure in the course of materializing it. Somoroff’s light is astronomically correct not only mystically inspiring. He has the benefit of scientific understanding of light and computer technology—Illumination I is computer generated, more particularly, Somoroff uses the computer to conceptualize it, which is not the same as illustrating it (that is, the computer is an envisioning rather than picturing device for him)--not available to Gothic architects. For the Abbot Sugar light was necessarily “mystical”—incomprehensible—apart from its “mystical” effect when deeply experienced. Somoroff appreciates the mystical benefits of light, and endorses the spiritual meaning traditionally accorded it, but he also brings modern science and technology to bear on it, and on art.

This may be beyond what was possible for Abbot Sugar, but it is not altogether discontinuous with his interests and methods. He notes the need for “geometrical and arithmetical instruments” to construct his complex church. One can’t simply build it intuitively, that is, pure faith alone will not get the job done. Similarly, Somoroff uses the instrumental reason embodied in the computer to design and plan Illumination I—a mathematically precise as well as inspiring work of mystical art, like the Gothic church. Somoroff’s streaks of light, carefully gradated, are in effect the ribs that distinguish Gothic vaulting from Romanesque volumes. They are counter-gravitational, like Gothic ribs. If, as has been suggested, standing upright gives us our first feeling of freedom, then relentlessly rising from the ground like a Gothic rib or a section of Somoroff’s light gives us an elated sense of absolute freedom. There is a hint of the flying buttress as well in Illumination I, suggested by the way it forks at the apex, forming two small arches, as though to lend support to an invisible structure, if also spontaneously rising from the visible structure.The traditional Gothic church has three stern portals, while Somoroff’s chapel has one all embracing grand portal, rising into two arches suggestive of church towers, although obviously not as hard and intimidating, and thus seemingly less aloof if also distant. The arches look out on the surrounding world, the encompassing portal draws us in from it. The grand clarity of the pattern makes us realize that the structure is not as loose as the fluidity of the ribs of light might suggest. The difference between the Gothic church and Somoroff’s chapel raises the question of what the best geometrical form is for sacred space. Is the intimidating Gothic facade, solid for all its openings, and the grand Gothic interior behind it, full of solid columns however open, more spiritually convincing and evocative than Somoroff’s facadeless archisculpture, which is virtually all interior, its shape being a kind of shell on its interior openness, which is its spiritual core? Mircea Eliade suggests that the question can be answered independently of whether the space is ecumenical—pantheocratic, as it were—or set apart for those of the one true faith in the one and only authentic God. The issue is whether the space is truly cosmic in import, that is, an “opening toward the transcendent,” as Eliade says, or whether it remains so bound to the earth—so heavy with “gravity”—and closed in on itself that it becomes claustrophobic despite itself, and thus suggests the self-imprisonment that Fromm deplored. Is the Gothic church spiritually unresolved, and perhaps spiritually inadequate—that is, unable to unequivocally convey and sustain spiritual aspiration—whatever spiritual claims the Gothic arch makes on us, and whatever spirituality we may experience under the spell of the church’s interior light?

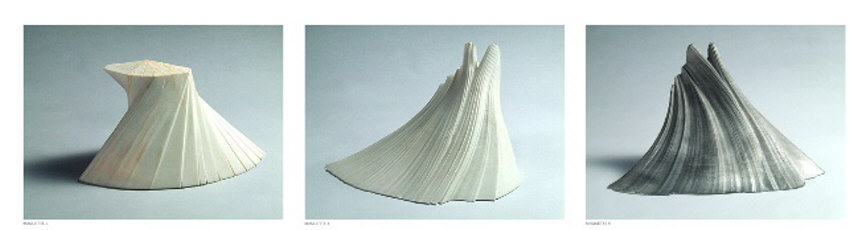

Maquettes, Illumination I