MK: How did you decide to become an artist? What sort of connection to art did you have, and how did that develop?

LS: I was always a creative kid, playing music, drawing, taking photographs and making soft sculptures with the furniture in our apartment. I recall the day I rang home from Bennington College to tell my parents that I was going to major in art, they took it well. My mother is a painter and my father used to run a nightclub, so they understood the creative drive.

MK: Your Self-Portrait , did you set out to do a self-portrait—or did you look at the completed work and then give it the title. What qualities in the piece resonated with you so that you called it a self-portrait?

LS: Something in that piece resonated as "self portrait,” it was not intentional, just a result.

MK: In larger pieces did you work with drawings and always with maquettes? Or did you move from drawings to the larger fabricated pieces?

LS: There was never a clear linear progression. I would let one way of working inform the other ways of working. I have always liked an organic approach to creating work.

MK: Steel, Plexiglas, canvass, bronze, wood and tar—you’ve worked with a variety of materials in your sculpture. For a while you were working a lot with tar. What did you like about it? What effect did it have?

LS: I loved working with tar for several reasons; it was easy to manipulate, resulted in a rich black surface and had no prior history as an art material. The field was open for me to experiment within. This is a recurring drive in my work.

MK: You said that after a while you found steel to be too ”didactic” and you moved to Plexiglas which you found more “feminine.” What do you mean when you say that steel is didactic? What was it at that moment that caused you to want a more feminine material with which to work?

LS: Moving from steel to Plexi was part of a long curve on which I am still running. Steel is immutable, never changing, even when it rusts it retains its materiality as steel. There is a long history in using it as an art material. It reeks of permanence and inflexibility. These are qualities by which most people choose to use steel, they are also the ones that turned me off to steel. I used Plexiglas as both a clear and translucent material. When the light changed, so did the material. It is responsive to changing conditions; in certain situations it can become invisible. I liked using a material that did not make pronouncements, but rather made suggestions.

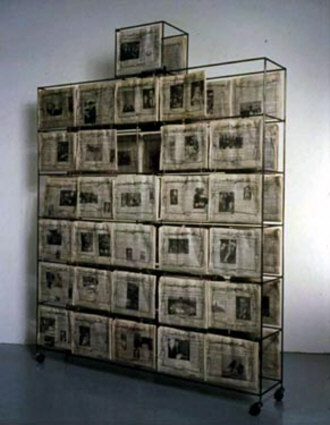

MK: 62 days from l992 of newspaper and steel is nothing visually like the work you’re doing now. It’s static, yet requires the passage of time and presents fragments of narratives in what can read of the papers. But it’s impossible to read all 62 at the same time—even to read two! Because it’s the news, connections exist from one to the other. Perhaps you had nothing of the sort in mind. Still, the work for me suggested possibilities of connections to your current work with memory and history. What do you think? Any reason for the number 62? Two months? Were the days consecutive?

LS: You are right on target. 62 Days is a precursor to my current work. I selected a 2 month period (Nov/Dec 2001) and kept copies of each NY Times paper which I read. If I did not read it, it was not included. Looking across them you see hundreds of new stories, many of which resonate as important world events. Each has shaped our lives in some way and then melded into our collective history.

MK: In Beyond Control (l992), steel, motor, chain—was this the first of your work that was in motion—Some of your large Plexiglas pieces, suspended would move, but not in the same way, of course.

LS: I was, and still am, very interested in the idea that we cannot stop time, only marginally slow it. In that sculpture there was a foot switch which you could depress and would stop the movement of the motors. When you released it, the motors started again and movement continued.

MK: Some of your sculpture and your drawings were abstract, but some works have a narrative possibility. Do you see any of your video works, the interactive or the purely generative, as having a narrative component—and if so where does that narrative reside? In the work or in the viewer?

LS: The generative video works are non-linear narrative pieces. The narrative is established by the viewer. The work is blind to the content it generates. The work presents possibilities and impossibilities, all dependent on context established by the viewer.

MK: You said you started using computer programs, CAD CAM, in order to do some of the commissions in which you worked with architects. Would you tell our readers how that led to your doing animation?

LS: I was working on a commission and needed a more efficient way to communicate with the client, the architect and the structural engineer. CAD was the easiest way to do this. I started off using animation software because the modeling interface really lent itself to making sculpture. Once I became proficient in that, I started to explore using virtual cameras and time (animation) as a way of exploring sculptural ideas. I found the process wholly intoxicating, spending days wrapped up in my virtual world.

MK: And please tell our readers how from that—finding the loop too confining—you moved to your more recent work?

LS: I would make the sculptural animations using a virtual camera to explore constructions. From that I would make looping animations. They were interesting at first, however they kept looping and I found that boring. The software could also simulate physics in virtual space. Next step was to take a group of sculptural objects and give each of them vastly different characteristics (gravity, mass, center of gravity, wind resistance, flexibility, etc) and drop them from up high in my virtual world. I situated cameras in my virtual world to film them as they bounced, flipped, knocked into each other and flew all over the place. This was the edited into another looping animation. This was much more interesting, however I was still left with a looping animation. From this came the seed for my current work, which was to create a series of conditions and let something interact with them over time. I would essentially create a hull though which things would flow and evolve on their own. I realized that this was also what I was trying to do with Plexiglas, namely, let something change on it's own accord. I did not want to control explicitly what took place (as I did in steel) instead I wanted it to grow an develop on its own.

MK: In Merge 2003, you said, “The flywheel was the movement” in front of the camera and that the person in front of the camera becomes the content. Was that a sort of discovery? Were you influenced by other new media artists in the construction of interactive video? Reacting to the sort of work they were doing?

Interview Continues

Self Portrait l989

wood, canvas, tar 42” x 35” x 18”

62 days

1992 / steel, newspapers. 82" x 73" x 13"