Decapitation Drawing & Quartering Firing Squad Flaying Starvation

Zhi Lin

Summer 2006

Details and Studies relating to the scrolls: "Five Capital Executions in China"

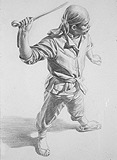

A man leading a horse, study for Drawing and Quartering 2000 graphite on paper 11 x 8

Two men kneeling and

tied up, study for Decapitation 1993

graphite on paper 11 x 8

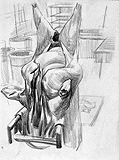

Carcasses in a

slaughterhouse, study for Decapitation 1993

graphite on paper 8 x 11

Three different aspects of a manís head, study for Starvation 1996 graphite on paper 8 x 11

A young man and a

middle aged man, study for Starvation

1996 graphite on paper 8 x 11

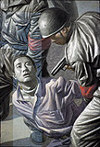

Detail of Starvation, a boy.

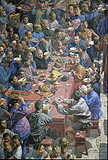

Detail of Starvation, feasting table.

2

Note to Readers: Due to the size and complexities of the works discussed, you will need to view them in a separate window. You can click on a scroll above to open a larger view. If you would like to read and view without shifting back and forth, on a PC compatible computer, simply right click the image desired above and choose "Open in New Window."

Interview Continued:

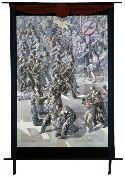

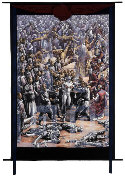

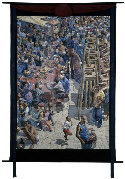

ZL: The elements that visually and conceptually "frame" the painting are its black border, red curtain, and blue ribbons inspired by Tibetan Buddhist thanka paintings. The thanka painting functions as revealing truth and as giving guidance to those who seek it. Therefore in the Five Executions, I use this device to show the true and complete face of the "civilized" human being. The image of an influential figure in Chinese thought is printed on the blue ribbons for each of the executions. Their philosophies have brought so many social revolutions to China that they reshaped Chinese history many times. Yet the brutality in the culture has continued without change. The raised red curtain is a symbolic challenge to the tradition that domestic shame should not be made public. The curtain functions as a barrier to cover the entire true character of our human being. This is the curtain that must be raised.

PC: Would you tell us a bit about the worldview behind these scrolls? Some political? Some of the human condition? What are the screen painted motifs over the canvasses? If they are weapons what are they? Are they the same from canvass to canvas? How did you choose them?

ZL: In the project, I used many cultural symbols from the history of China. The silk-screen image printed over each of the five paintings depicts an ancient Chinese weapon. This approach reflects my critique of Post-Modernism. The image is based on a set of unearthed ceremonial weapons in 1978 in China, Shan character shaped ji with spiraled cloud patterns. Each of them is 47 in. high, 29 in. wide, 110 pounds, and dates back to 475-221 (B.C.). Within the flat weapon image I translated the painting, which is painted in the Western style, into a line drawing that reflects a Chinese tradition. I use the abstracted symbol of a weapon to represent killing and oppression. And in my opinion, so much of the history of China has been shaped by death that history can only be seen through the symbolism of that kind of device (it references to Lu Xun's writing, A Madman's Daily). Through the use of transparent overlay, I see the symbol as always present, both obscuring and defining the character of our human being. The people being slaughtered are undercurrents of the history river, they are no longer visible, but they are essential in the shaping of our history and humanity.

PC: You've said, "The transparent and subtle overlay signifies the symbol as always present, both obscuring and defining the character of our human being." Could you explain a bit more about that?

ZL: In my opinion, so much of the history of China has been shaped by death that history can only be seen through the symbolism of that kind of device. It references to Lu Xun's writing, A Madman's Daily. Through the use of transparent overlay, I see the symbol as always present, both obscuring and defining the character of our human being. In other words, the people being slaughtered are undercurrents of the history river, they are no longer visible, but they are essential in the shaping of our history and humanity.

PC: Looking at the color studies for these scrolls, I was struck by the changes you've made in color. Will you talk about those decisions?

ZL: The main reason for the change is footed in my journey in learning the painting practice. I chose to paint the five paintings in the project one at a time, so that as my understanding of the painting language progresses, my painting is improving one at a time.

PC: You returned to CNFA in Hangzhou three years after your BFA. What sort of art were you doing in the meanwhile?

ZL: From 1982 to 1987, I began to experiment in making prints and paintings based on Chinese calligraphy; it was abstract. I used Chinese characters as the compositional structure to make abstract paintings and prints, and it was an attempt to study Western art through my understanding of Chinese culture.

PC: From there you went to the Slade School of Fine Art in London for a second MFA. While you were in London, Tiananmen Square demonstrations (l989) occurred and violent reaction of the government--Would you tell us, please, a bit about your experience watching all this on television. Was it a solitary experience, or were you with others, and what sort of discussions followed?

ZL: On June 4, 1989, when tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square, the People's Liberation Army began firing at the peaceful crowds. The blood of young Chinese students soaked the ground of the square and streets in the ancient city of Beijing. I was on the top deck of a bus that was traveling along Oxford Street in London when I heard the breaking news live from my handheld radio.

I remembered that I asked myself a question: why the government officials could order its army to slaughter the students -- their own children or grandchildren? It was because they had labeled the students as counterrevolutionaries, and with that label, the thousands of students and their supporters were no longer regarded as human beings. This is not unique to the communist regime. Many governments labeled the reform-oriented student movements with deadly titles in order to suppress the student led social reforms. There have been many such incidents around the world since WWII. Answer Continues on Next Page.