Decapitation Drawing & Quartering Firing Squad Flaying Starvation

Zhi Lin

Summer 2006

Links

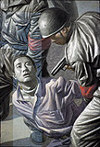

Assassination of St. Peter Martyr

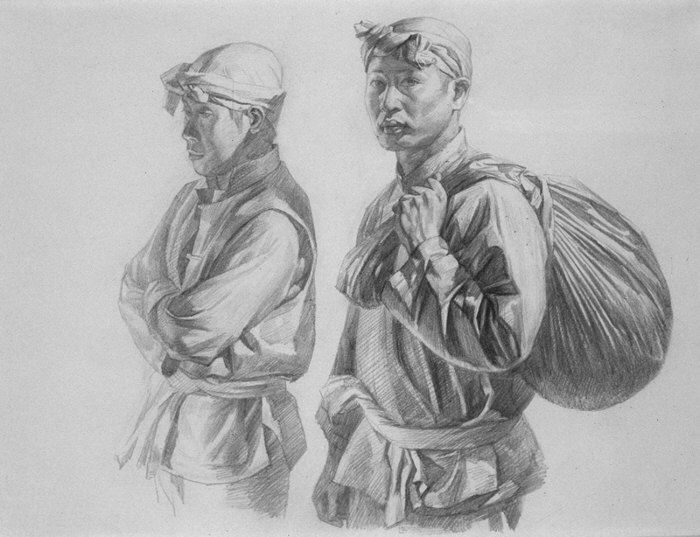

Vietnamese Marine Shooting Vietcong

The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus

4

Interview Continued:

ZL: There was a very important conjuncture that I encountered between Western painting and Chinese literature, when I stood in front of Giovanni Bellini's, Assassination of St. Peter Martyr (1509) in London in August of 1989, two months after the massacre. On that day, the painting became so familiar to me; it made me recall Lu Xun's novel Medicine. Lu Xun (1881 - 1936) was one of the most important writers in 20th century Chinese literature. He was supposed to be a doctor. One day, while he was studying at a medical school in Japan, he was outraged by a shot of news footage in which Japanese soldiers were beheading a squad of Chinese POWs as the fellow indifferent compatriots watched. He gave up his medical career, which is to cure the human body and became a writer, in his words, to wake up his people's souls. In a scene from his novel Medicine, a revolutionary was executed and it did not matter to the locals, except that people rushed to the site and wanted to use the blood from the dead to cure their illness.

Both Lu Xun's work and Bellini's painting reminded me that there is something within each of us; it can be described best in the German word "schadenfreude" for pleasure in the misfortunes of other people. Sartre's famous line, "Hell is other people." Schadenfreude belongs to the dark impulses of human nature, and exists within each of us as a part of human condition. Because of that, many of us support capital punishment; and without any rewards (such as enabling someone to reach heaven) many of us do not care about human rights violations, and the poor and disadvantaged within this country and beyond. In both works, the indifference displayed by the bystanders as well as the unavoidable duality made the suffering more unbearable. In one of W. H. Auden's poems, he articulated it better than anyone.

PC: In Starvation those being starved are next to a banquet. In the background of Firing Squad crowds pass by on bicycles. Will you comment?

ZL: "Five Capital Executions" presents brutal torture methods used in China. In the series, I create and mix an intertwining of images and dichotomies in order to reveal an idea of duality. A festival atmosphere or a street scene surrounds an execution with bloody tortures. Soldiers wield weapons as musicians play their instruments or performers display dragon dances and bystanders carry out their daily routines. Traditional Chinese painting composition combined with the Western method of representation deals with the duality of seemingly contradictory elements and references that bind the horrific with aesthetic concepts of beauty. Duality, as a philosophical idea, pales next to humankind's true face, characters and propensity. No work that seeks to strike at the human psyche can present the horror of cruelty without including our capacity to condone, justify or sanctify it. The contradictions represented in my paintings are to remind us of our own participation in the crowd.

PC: Would you say something about the perspective in these pieces, both of the artist and the viewer of the scrolls, how we - and you as the artist are positioned in relation to what's happening--and to whom.

ZL: I employ a series compositional strategies to draw the viewer into the picture and accentuate its immediacy. As Dr. Schall, from the Nelson-Atkins Museum, has pointed out, in my composition, I leave open space in the foreground and carry it upward into the image; include figures looking out at us -- acknowledging our presence as witness to the executions; and make a steep perspective that tilts the scene upward, pushing the action toward the picture plane. The first two strategies are borrowed from Baroque paintings of the seventeenth century, while the third has its source in Chinese art: a so-called "bird's eye view" composition, which is common to Chinese monumental landscape painting. A good example of the perspective is Guo Xi's Early Spring (Northern Song, 1072). It is also in the pre-Renaissance traditions of the West, and in the Modern rejection of Renaissance space. The purpose of all the strategies is to allow the viewer to become a part of the crowd. As the audience stands in front of the painting, they are surrounding the execution with the crowds in the painting and forming the circle around the torture. As the audience views the painting from close range, they can overcome the barriers of time, and they are confronted with the killing grounds in person. I hope it will allow them to think and to react. That is one of the main reasons why I chose to work on this large scale; people can almost walk into the scene.

PC: Seems to be a mixture of the surreal in with these grim images: the levitating figures in Flaying?

ZL: The levitating figures are acrobats. If you look carefully, in each of the five paintings, there is one segment that is hanging over, flying out, or levitating above the mess. It is a composition device - to bring viewers into the painting from the top of the composition. By doing so, I allow my viewers to enter each of the five paintings from both top - Chinese landscape perspective, and the bottom - more common in Western perspective.

PC: In these scrolls have you included portraits of others--or self-portraits as Michelangelo--did in the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, with a self-portrait in the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew or Biagio Da Caesena, according to Vasari, as Minos.

ZL: In the project, I began to introduce or include self-portraits in the paintings. The practice started in the second painting, Decapitation, with the centered figure - who has been beheaded - however I didn't show my face. In Firing Squad, again, I tried to paint myself as the center figure. There are multiple self-portraits in the fourth and fifth paintings, Starvation, and Drawing and Quartering, and I painted myself in two different characters: a spectator or prisoner. The painters, in Europe, have a long tradition of integrating portraits of themselves among the spectators (assistenza) in their religious compositions. They were meant to be understood as a reference to their status as authors, but first and foremost should be seen as an expression of personal hope for salvation. Gradually, they furthered to depict themselves as the spectators (in assistenza), working themselves into the scenes and occasionally painted themselves into the role of one of the protagonists, a practice that would be maintained for centuries.

PC: How were you influenced by traditional Chinese landscape painting?

ZL: The vertical format and the overall composition for each of the five paintings in the project are deep in debt to traditional Chinese landscape painting - more specifically, monumental landscape painting. I would like to address another issue here that is about the birds' eye view perspective in Chinese landscape painting. It is very common to find that kind of perspective in many Buddhist painting and frescos in Medieval China. In many compositions, the bird's eye view is combined with eye-level view perspective. It often is to illustrate a believer's journey to paradise -- through experiencing and examining the sinful world by looking down upon it as a bird.

As a matter of fact, in the project, searching for metaphors to critique social ills drove me to study the ancient Chinese practice of using coded images and phrases to convey political dissent and social commentary in paintings and literature. Similarly, I explore visual phrases containing ideas, and compositions for constructing concepts in Western art. The composition references for each of the five paintings in the project are: Flaying -- Giovanni Bellini, Assassination of St. Peter Martyr (1509), Rogier van der Weyden, Descent from the Cross (1435); Decapitation -- Hans Memling, Altarpiece of two St. John (1433-94); Firing squad -- Caravaggio, Burial of St. Lucy 1608), Manet, Execution of Maximilian (1867), Edward Adams, Vietnamese Marine Shooting Vietcong (1969); Starvation -- Tintoretto, The last Supper (1592-94); Drawing & Quartering -- Dieric Bouts, The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus (1475), Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracles of St. Francis of Paola (1627), and Goya, 3rd of May, 1808 (1814).

PC: You've taught yourself the art of calligraphy--how, if at all, do you use it in your painting?

ZL: Certainly, there is a profound impact to my work from my learning and practice of Chinese calligraphy. A short answer to the question is to quote Michael Sullivan's words. Once he wrote "not only is a man's writing a clue to his temperament, his moral worth, and his learning, but the uniquely ideographic nature of Chinese script has charged each individual character with richness of content and association ..."

PC: How does your philosophy relate to your teaching methods? What do you work on with your students?

ZL: In my teaching of drawing and painting classes, I attempt to build the students' understanding and confidence through exercises which isolate and clarify particular aspects of visual art. These exercises develop basic skills and give a wide variety of experiences, but most importantly, they investigate the underlying thought process of vision and problem solving. To me, teaching is not merely presenting course materials to the students in the classroom, rather it should be an endeavor to develop and recognize each student's potential, and to assist the student in achieving his or her unthinkable goals and expectations. As a native of China, my teaching philosophy and the way that I teach reflects my understanding of Confucius' teachings. In addition, my teaching, I would like to enable the student to make academic connections between visual arts and other fields in humanities and social sciences. In fact, my work presents to our students one of the social roles of the painter, using visual literacy for advocating, advancing, and championing the positive social and environmental changes in today's society.

PC: You've spoken about "cultural colonialism." Would you say more about that, especially as it relates to art?

ZL: For the past twenty years, curators, and art dealers from America and Europe have had enormous political, cultural, professional, and economic power and impact over the artists in China. Many American and European curators and art dealers went to China, without having any knowledge or understanding of Chinese culture, only to try to find something they are familiar with or that they have knowledge about. It is very similar to the way that some of our fellow Americans go to China or France and only eat in McDonald's restaurants. Actually, they've gone beyond that. With the lure of career enhancements and financial benefits, they've directed some of the Chinese artists to produce certain art works for their organized exhibitions. They are promoting the kind of art that they want to see in China for the advancement of their ideologies and careers. There is not so much difference between them and the British soldiers in the 19th and early 20th century, who didn't speak a word of the occupied land, and lectured the locals about how to run their country.

Finally, I would like to mention a few words about my current project, Invisible People: Chinese Railroad Workers. The project "Invisible people" is centered on the bitter history of Chinese workers in the construction of the American transcontinental railroads in the second half of the 19th century. The project raises social awareness of the Chinese workers' contributions to America. It challenges the audience's history and cultural awareness, and furthers their understanding of America history. Most importantly, I hope that the project will inspire the audience to critically examine the current Sinophobic movement with a historical perspective and to prevent our history from being repeated.End of Interview Previous Page