A New Sacred Space: Michael Somoroff’s Illumination I by Donald Kuspit

In other words, Illumination I satisfies the need for transcendence, even if the spectator doesn’t know that he or she has the need. Illumination I articulates the pressing need for transcendence—all the more so these “descendental” days—and thus invites the spectator to satisfy the need through it. Seeing the light in and through Illumination I the spectator confirms that it is sacred—a sacred space in which the spectator can experience his or her inner sacredness. Supposedly nothing is sacred in a secular world—we are all profane in the “iron cage,” the term Max Weber used to describe society after it had been modernized by science and technology (an ironically enlightenment, as Weber suggests, for it made the world uniformly gray)--but some works of art still seem sacred, and demand a spiritual response.

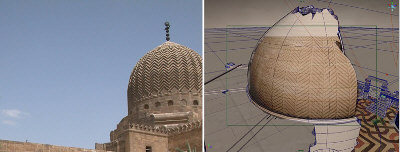

The Rothko Chapel, Houston, 1965-66 is a standard modernist structure designed by Philip Johnson. Its octagonal shape is a familiar cosmic signifier; its use in such different churches as San Vitale, Ravenna, 526-47 and Santa Maria della Salute, Venice, 1631-48 indicates as much. In contrast, Somoroff’s Illumination I—its fluid shape tracks the path of the light at the Rothko Chapel the day the United States invaded Iraq, as it comes through the ruins of a computer-constructed mosque, an elaborate convergence of the Rothko Chapel plans and news photographs of destroyed mosques in Iraq and Afganistan—is in effect an alternative chapel or sacred space. In a sense, it is the luminously alive, vibrant dome the dull, not to say unimaginative Rothko Chapel architecture lacks. San Vitale consists of two octagons, the inner one a dome rising above the outer one to provide light to the interior. The higher octagon lets heavenly light into the lower earthly octagon. The light blesses the worshippers below, raising their spirits to the sacred heights from which it emanates. If Somoroff’s monumental “archisculptur”(3) can be read as a kind of dome, then it is an unconventional dome displaced to the outside of a conventional chapel. All the more so because it is more geometrically ingenious—and also, paradoxically, organically resonant, for it seems to flower in the light it embodies and embraces—than Johnson’s architecture. Somoroff’s archisculpture is clearly a more adequate symbol of cosmic nature than Johnson’s simplistic octagon. Its spatial autonomy confirms that it has the spiritual authority Johnson’s simplistic structure lacks. And, also, as I will argue, the spiritual vitality—joyously extroverted power—that Rothko’s paintings, with their aura of permanent despair, suggesting interiority at a complete spiritual loss, lack.

News photo of Khanqah, Cairo and Virtual Mosque Construction

The Rothko Chapel is permanent home to fourteen monumental paintings by Rothko each implicitly a “representation” of one of the fourteen Stations of the Cross, and each inviting one to immerse oneself in its subtle gloom—to experience, in effect, the “Dark Night of the Soul,” one’s own soul. H. H. Arnason notes that “At the end of the fifties, Rothko began to move away from bright, sensuous color toward deeper, more somber hues. By the late sixties, the mood of his work had darkened still further, expressing his conviction that, even at its most abstract, art could convey a sense of ‘tragedy, ecstasy, and doom’.”(4) Rothko was born in 1903; he committed suicide in 1970. The Rothko Chapel paintings were made in 1965-66, a few years before his death. They seem to announce and anticipate it.

Rothko’s paintings became darker and darker as death came closer and closer. The more he realized its inevitability, the darker the paintings became. “Almost uniform in their deep black and red-brown,” as Arnason observes, they are profoundly entropic in import.

As Rudolf Arnheim writes, entropy is evident in “the emptiness of homogeneity” and in “disorderly destruction.” One might say that there is a self-destructive emptiness in the Rothko Chapel paintings—certainly a strong tendency to homogeneity or, as Arnason says, absolute uniformity. It is a sort of catabolic reductio of absurdum of simplicity, to use Arnheim’s language, a level of order so low that it is barely visible.