A New Sacred Space: Michael Somoroff’s Illumination I by Donald Kuspit

The Rothko Chapel paintings are all but inert, suggesting an immobilized, dead-ended psyche. They seem to move in the light, but it is the light that moves in them, and then ever so slightly. They are too heavy with despair to move on their own. They have a peculiar inner light, but it is too dim and limited to stir, even when outer light seems to bring it out, as though to awaken it to its own uncanniness. I think the outer light makes their bleakness explicit. The Rothko Chapel paintings “have a less amorphous, harder-edge appearance than Rothko’s earlier abstractions,” Arnason writes. To me, this loss of gestural intensity confirms that they crystallize Rothko’s despondency. They reify his sense of nothingness, more particularly, meaninglessness, including the meaninglessness of painting. They convey Rothko’s feeling of abandonment and of being abandoned by painting. He had devoted his life to it, but it can do nothing more for him and he can do nothing more for it.

Obsessively redundant, however subtly differentiated, the Rothko Chapel paintings dwell on the same note of doom and gloom, varying it endlessly but never departing from it. Frankly, I don’t see ecstasy in them, only muted terror, which is not the same as tragedy, which always involves a moment of self-knowledge. Their blankness suggests resistance to self-knowledge, perhaps because Rothko felt that his self had become a void, and thus there was no self to know. Self-destruction is sometimes a defense against self-knowledge, as well as an enactment of the void that the self has become. That is, confirms the feeling of being unreal and uncreative. As D. W. Winnicott suggests, they are inseparable. Taken together, the Rothko Chapel paintings are a monument to depression. They are a sort of requiem celebrating living death, in expectation of actual death. They pay homage to melancholy, as though it was the only significant feeling. Art historically speaking, their tendency to colorlessness signifies the death of color field painting. Abstraction has become decadent in the Rothko Chapel paintings, which makes them more poignant, but also suggests its diminishing aesthetic and expressive returns. Abstract painting loses expressive power in the Rothko Chapel paintings, especially compared to the dynamic early abstractions of Kandinsky, the founding father of gestural abstraction. They have lost inner tension, and with that life. As Arnheim writes, entropy carries tension reduction to a nihilistic extreme, resulting in a deadening effect: the Rothko Chapel paintings are inwardly dead however much they may be brought to nominal life by the artificial light in which they are bathed.

Somoroff’s three-dimensional Illumination I is the vigorous “countertendency” to Rothko’s two-dimensional paintings, to use Arnheim’s word, an “anabolic...structural theme, which introduces and maintains tension.” It is the creative alternative to Rothko’s decreation of painting. It throws down the gauntlet to Johnson’s sterile architecture as well as Rothko’s bleak paintings, challenging their reductive—not to say simplistic—modernism with its postmodern complexity. If modernist architecture depends on what Charles Jencks calls “univalance,” and if modernist painting entropically tends toward similarly “simplified values,”(6) as the Rothko Chapel paintings suggest—they are not alone in this, as Barnett Newman’s paintings make clear—then Somoroff”s archisculpture is postmodern by reason of its multivalence, for Jencks the characteristic sign of postmodernism.

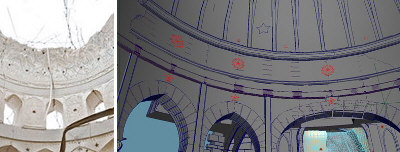

Al-Aksar News Photo and Virtual Mosque Construction

As such it is a declaration of independence from both the architecture of the Chapel and the paintings in it, however much Illumination I is in tense relationship with them. Indeed, it becomes—in spirit if not the letter—the linchpin of the whole Chapel, in effect completing it by dialectically integrating its parts. Illumination I in effect sculpturally resolves the difference between Johnson’s architecture and Rothko’s paintings—the former has eight facets, and the latter are in effect fourteen facets of the same grand painting—through its own highly faceted structure. Extreme reductionism is a sign of creative exhaustion, a way of continuing to make an art that has lost inner necessity, a technique of survival when there is no sense of purpose, an endgame method of keeping the game going when it has been lost. If Rothko’s paintings signify what Arnheim calls “collapse by exhaustion”—their minimalist aspect, that is, sense of collapsing in on themselves, suggests as much—then Somoroff’s archisculpture suggests resurrection by way of infinitely expansive, surging energy, and is thus “maximalist” in character.(7)